Motivation

Machine learning (ML) has transformed our lives![]() , touching everything from our smartphones to healthcare. We rely on ML techniques to talk to chatbots for information, search the internet, and detect diseases. As more and more use cases emerge, more of our data is needed to power ML, and privacy concerns develop even further. Technology companies need access to our data to enable these applications and provide meaningful services. However, some types of data, like medical or financial, can be more sensitive than others. To address these concerns, security practitioners have been developing the privacy-preserving machine learning (PPML) paradigm, where data owners can protect their privacy while still taking advantage of the power of ML.

, touching everything from our smartphones to healthcare. We rely on ML techniques to talk to chatbots for information, search the internet, and detect diseases. As more and more use cases emerge, more of our data is needed to power ML, and privacy concerns develop even further. Technology companies need access to our data to enable these applications and provide meaningful services. However, some types of data, like medical or financial, can be more sensitive than others. To address these concerns, security practitioners have been developing the privacy-preserving machine learning (PPML) paradigm, where data owners can protect their privacy while still taking advantage of the power of ML.

In our previous blog post about Curl![]() , we explored how secure multiparty computation (MPC) enables two companies to evaluate a machine learning model privately. Using Curl, a company that has proprietary inputs (e.g., disease risk prediction) can perform privacy-preserving inference on a proprietary model (e.g., ChatGPT) that is held by a different company while keeping both the sensitive input data and the private model weights secret from each other. Unfortunately, MPC requires both parties to be actively involved with the computation, requiring significant computational resources and communication bandwidth. However, in some cases, the client might have limited computation resources (e.g., a phone or a laptop) or limited bandwidth and want to completely offload the computation to the more powerful server that owns the model. Let’s take, for example, an individual who has taken multiple tests and wants an ML model to verify if there is anything worrisome that a doctor might have missed. Of course, they would like to keep their medical data private, but still use the machine learning model for additional peace of mind. In cases like this, delegating the computation while preserving the privacy of the clients’ inputs is crucial as engaging in MPC might hinder adoption for some clients.

, we explored how secure multiparty computation (MPC) enables two companies to evaluate a machine learning model privately. Using Curl, a company that has proprietary inputs (e.g., disease risk prediction) can perform privacy-preserving inference on a proprietary model (e.g., ChatGPT) that is held by a different company while keeping both the sensitive input data and the private model weights secret from each other. Unfortunately, MPC requires both parties to be actively involved with the computation, requiring significant computational resources and communication bandwidth. However, in some cases, the client might have limited computation resources (e.g., a phone or a laptop) or limited bandwidth and want to completely offload the computation to the more powerful server that owns the model. Let’s take, for example, an individual who has taken multiple tests and wants an ML model to verify if there is anything worrisome that a doctor might have missed. Of course, they would like to keep their medical data private, but still use the machine learning model for additional peace of mind. In cases like this, delegating the computation while preserving the privacy of the clients’ inputs is crucial as engaging in MPC might hinder adoption for some clients.

Fully Homomorphic Encryption

Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) is better suited for this task; in FHE, the client can encrypt their data locally and send it over to a remote server, which runs the computation and sends the encrypted results back to the client. Unlike traditional forms of encryption, data is protected at all times: at rest, in transit, and in use. The server learns nothing about the input data, intermediate values, and the final results of the computation. At the same time, the client only receives the results of the ML model and learns nothing about the ML model weights themselves. Most FHE schemes offer only addition and multiplication over ciphertexts. On the other hand, non-linear functions (which are a core part of ML models) need to be computed as costly polynomial approximations that can be evaluated with the native arithmetic operations. Fortunately, some FHE cryptosystems can evaluate arbitrary functions over ciphertexts using lookup tables using a technique called programmable bootstrapping (PBS). With PBS, non-linear functions can be evaluated directly, without relying on the aforementioned approximations! Under the hood, PBS encodes the target non-linear function as a lookup table (LUT) that consists of all possible inputs and the corresponding outputs. Take, for example, the square function f(x) = x![]() , defined for x in {1, 2 ,3, 4}. We can create a LUT for this function as:

, defined for x in {1, 2 ,3, 4}. We can create a LUT for this function as:

| Input | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Output | 1 | 4 | 9 | 16 |

This LUT encodes information required to map the function inputs to the desired output values and we can “look up” the output based on the input. However, PBS becomes extremely costly with increasing input and output ranges; specifically, the larger the table and the larger the numbers in the cells grow, the more impractical PBS becomes.

To address this challenge, we present Ripple: a framework that introduces different approximation methodologies based on discrete wavelet transforms (DWT) to decrease the number of entries in homomorphic lookup tables while maintaining high accuracy.

Discrete Wavelet Transforms (DWT)

A discrete wavelet transform is a signal processing method that divides a signal into approximation and detail coefficients. Most of the information is captured by the approximation coefficients while the detail coefficients contain information about small errors in the signal. This process is reversible; the original signal can be reconstructed without any information loss using the approximation and the detail coefficients. Another property of DWT is that it can be recursively applied; if we take the approximation coefficients of the approximation coefficients, we get an even smaller set of approximations! This way, the signal can be compressed to the desired size and corresponding accuracy level.

The most basic DWT method is called Haar. Here, a linear transformation is applied to the signal, and essentially breaks the signal into sums and differences. The points that are close to each other, namely the ones that share the higher-order bits, have the same approximation under Haar. This makes it easy to apply under FHE, namely, we only need to see the higher-order bits to compute a number’s Haar approximation. We can just truncate the number, i.e., cut out the lower-order bits and apply a lookup table protocol with the higher-order bits.

Haar’s simplicity also becomes its weakness because it does not make use of the lower-order bits. Biorthogonal is a more complex DWT that uses weighted averages between the lower-order bits and the higher-order to approximate values. This way, it captures more information about the number, hence leading to a better approximation. As this is a more elaborate technique, it decreases the speed of execution, but at the same time, it greatly enhances the accuracy of the approximation.

The Ripple Framework

As mentioned earlier, evaluating non-linear functions can be done in FHE using PBS, however, as accuracy requirements increase, this becomes exponentially costly, to the point of becoming impractical. Our observation in Ripple is that we can rely on DWT approximations to reduce the size of the lookup tables to a practical range without sacrificing accuracy. We propose two methods, using Haar and biorthogonal wavelets, to compress lookup tables resulting in significantly reduced runtimes.

To reduce the size of the look-up tables that need to be evaluated through PBS even further, we introduce two optimizations, exploiting the symmetry and convergence properties of commonly used functions.

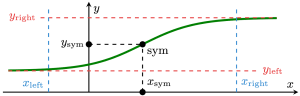

- First, when a function is symmetric around a point (

,

,  ) like the image above, by evaluating one side of the domain, we can deduce the evaluations of the other side. For example, tanh(-x) = -tanh(x). This allows us to half the size of the look-up tables, or in a different interpretation, double the precision if we keep the look-up table size the same.

) like the image above, by evaluating one side of the domain, we can deduce the evaluations of the other side. For example, tanh(-x) = -tanh(x). This allows us to half the size of the look-up tables, or in a different interpretation, double the precision if we keep the look-up table size the same. - Next, commonly used functions like sigmoid, tanh, or the error function converge to a constant or a polynomial function outside of some bounds. In the image above, the limits are depicted as

and

and  , and the function is negligibly different from the limits outside

, and the function is negligibly different from the limits outside  and

and  . For example, sigmoid converges to 1 as the inputs increase, and it converges to 0 as the inputs decrease. Therefore, given the accuracy requirements, we can choose a threshold, after which we just return the limit. As a result, we only have to use a lookup table in a small region, namely between

. For example, sigmoid converges to 1 as the inputs increase, and it converges to 0 as the inputs decrease. Therefore, given the accuracy requirements, we can choose a threshold, after which we just return the limit. As a result, we only have to use a lookup table in a small region, namely between  and

and  . This greatly reduces the domain, speeding up the PBS execution time while not sacrificing the accuracy.

. This greatly reduces the domain, speeding up the PBS execution time while not sacrificing the accuracy.

Together these two optimizations result in significantly reduced accuracy to runtime tradeoff. In the table below, we show the effect of these optimizations for three non-linear functions (sigmoid σ(x), the error function erf(x), and the hyperbolic tangent tanh(x)) for different word sizes, look up table (LUT) sizes, and precision sizes. For Haar, we observe a 30-500x reduction in approximation errors, while for biorthogonal the errors go down 2.2-132x. The reason that these optimizations are more effective for Haar, is that Biorthogonal already approximates really well!

| Operation | word size | precision | LUT size | Haar | Biorthogonal | ||||

| Baseline | Optimized | Diff. | Baseline | Optimized | Diff. | ||||

| σ(x) | 24 | 16 | 12 | 7.82e-3 | 2.57e-4 | 30x | 3.6e-5 | 1.65e-5 | 2.2x |

| erf(x) | 3.52e-2 | 1.11e-3 | 32x | 3.34e-4 | 3.43e-5 | 9.7x | |||

| tanh(x) | 3.12e-2 | 9.82e-4 | 32x | 2.67e-4 | 3.01e-5 | 8.9x | |||

| σ(x) | 32 | 20 | 16 | 7.81e-3 | 1.61e-5 | 485x | 3.16e-5 | 1.04e-6 | 30x |

| erf(x) | 3.52e-2 | 6.93e-5 | 508x | 3.16e-4 | 2.15e-6 | 147x | |||

| tanh(x) | 3.12e-2 | 6.15e-5 | 507x | 2.51e-4 | 1.9e-6 | 132x | |||

In our next experiment, we investigate the approximation of different non-linear functions such as square root, logarithm, etc. under different look-up table techniques (quantization, Haar DWT, and Biorthogonal DWT). More specifically, we observe that the two DWT techniques of Ripple outperform quantization by a wide margin, especially the errors of the Biorthogonal DWT drop quickly for LUT sizes bigger than ![]() .

.

Finally, we compared the Ripple framework with state-of-the-art works (TFHE-rs![]() , HELM

, HELM![]() , Google Transpiler

, Google Transpiler![]() , and Romeo

, and Romeo![]() ) for a logistic regression inference benchmark with four attributes and word sizes of 16, 24, and 32 bits.

) for a logistic regression inference benchmark with four attributes and word sizes of 16, 24, and 32 bits.

For 24 bits, the arithmetic mode of HELM as well as both modes of the Google Transpiler are

not applicable (N/A) as they rely on native word sizes. Lastly, for 32 bits, the TFHE-rs baseline is also N/A as the resources required for the LUT are impractical. Related works utilize a low-degree polynomial approximation for sigmoid. We observe that:

- Ripple (red and green bars) is significantly faster than related works and also outperforms the TFHE-rs baseline (purple bar) using the full-bit width.

- The only exception to this is with W = 16 bits (first subplot above), where the baseline outperforms the Biorthogonal DWT; however, for 24 bits, the Biorthogonal DWT exhibits lower latency than the baseline.

- To achieve high accuracy with our chosen dataset, we utilize all eight attributes with a wordsize of 24 bits. For this classification, all modes achieve 100% accuracy; the baseline latency is 13.3 seconds per inference, while the Biorthogonal DWT variant classifies in 7.8 seconds.

- Lastly, the quantized variant that truncates half of the bits of the LUT input exhibits a latency of 6.2 seconds, while the Haar DWT slightly outperforms this with a latency of approximately 6 seconds.

What’s next?

We have explored applications of machine learning and running LLMs within Curl, but we are also interested in extending this exploration to the realm of FHE. FHE offers unique advantages in scenarios where a client prefers to offload computation to a powerful server while maintaining privacy, without directly participating in the computation.

Read our full Ripple paper here![]() .

.

Keep your eye out for our upcoming blog post called Wave Hello to Privacy, in which we will explore how we can use function secret sharing to greatly reduce the runtime of lookup tables in secure multiparty computation. Curl was a first step in that direction, and Wave takes it one step further by achieving speedups to the DWT lookup table protocols. In Wave, we explore if we can build a protocol that is even faster than Curl or Ripple while also reducing the communication overhead during pre-processing.

Ripple, Curl, and Wave serve as foundational building blocks with significant implications for the future of privacy-preserving AI. As AI technologies advance, they enable the development of AI agents – autonomous software systems capable of perceiving their environment, reasoning, and taking action to achieve specific goals. These agents are increasingly employed in applications such as virtual assistants, recommendation systems, and decision-making tools. However, when tasked with handling sensitive information, it is imperative that they operate in a privacy-preserving manner to prevent unauthorized access, cyberattacks, and censorship. Ripple’s ability to accelerate FHE while maintaining high accuracy can be used to empower AI agents to process encrypted private data securely without compromising user confidentiality. This capability is especially critical in domains like personalized healthcare, financial advising, and secure personal assistants, where data sensitivity is paramount, opening the door to broader adoption of privacy-preserving AI technologies.

References

- Unlocking a New Era of Private AI for Everyday Use

https://nillion.com/news/1395/ - A New Wave of Privacy-Preserving Large Language Models

https://nillion.com/news/1175/ - Manuel B. Santos, Dimitris Mouris, Mehmet Ugurbil, Stanislaw Jarecki, José Reis, Shubho Sengupta, and Miguel de Vega.

Curl: Private LLMs through Wavelet-Encoded Look-Up Tables.

In Conference on Applied Machine Learning for Information Security (CAMLIS), 2024.

PDF: https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/1127.pdf

Code: https://github.com/jimouris/curl - TFHE-rs: A Pure Rust Implementation of the TFHE Scheme for Boolean and Integer Arithmetics Over Encrypted Data, Zama, 2022

Code: https://github.com/zama-ai/tfhe-rs - Gouert, Charles, Dimitris Mouris, and Nektarios Georgios Tsoutsos. “HELM: Navigating Homomorphic Encryption through Gates and Lookup Tables.” Cryptology ePrint Archive (2023).

PDF: https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/1382.pdf

Code: https://github.com/TrustworthyComputing/helm - Gorantala, Shruthi, et al. “A general purpose transpiler for fully homomorphic encryption.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.07893 (2021).

PDF: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2106.07893

Code: https://github.com/google/fully-homomorphic-encryption - Gouert, Charles, and Nektarios Georgios Tsoutsos. “Romeo: conversion and evaluation of hdl designs in the encrypted domain.” 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC). IEEE, 2020.

PDF: https://eprint.iacr.org/2022/825.pdf - Gouert, C., Ugurbil, M., Mouris, D., de Vega, M., Tsoutsos, N.G. (2025). Ripple: Accelerating Programmable Bootstraps for FHE with Wavelet Approximations. In: Mouha, N., Nikiforakis, N. (eds) Information Security. ISC 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 15257. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-75757-0_14

PDF: https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/866.pdf

Code: https://github.com/NillionNetwork/ripple

Follow @BuildOnNillion on X/Twitter for more updates like these