The rise of genomic sequencing technologies has marked a new era in biological and healthcare research. The Human Genome Project, completed in the early 2000s, is a milestone of sequencing technologies to map the entire human genome ![]() . This motivates numerous fields of research and a wide range of applications including personal medical treatments

. This motivates numerous fields of research and a wide range of applications including personal medical treatments ![]()

![]()

![]() , paternity tests

, paternity tests ![]()

![]()

![]() , and cancer and infectious disease research.

, and cancer and infectious disease research. ![]()

![]()

![]() A fundamental challenge is measuring the similarity of sequences using Hamming distance, Jaccard similarity, Pearson correlation, and Euclidean distance. However, among these options, computing edit distance is often favored for several reasons across many scenarios.

A fundamental challenge is measuring the similarity of sequences using Hamming distance, Jaccard similarity, Pearson correlation, and Euclidean distance. However, among these options, computing edit distance is often favored for several reasons across many scenarios.

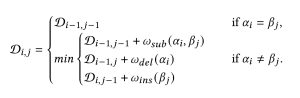

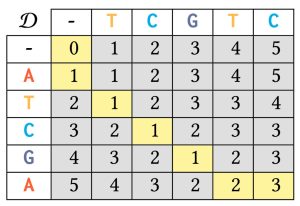

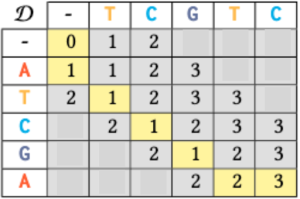

Edit distance (ED) is given by the minimum number of insertions, deletions, and substitutions to convert one sequence into another. This metric can be intuitively understood as representing the number of evolutionary events that may occur between sequences. The Wagner-Fischer algorithm is renowned for its efficacy in solving the edit distance problem using dynamic programming. This algorithm enables precise calculations of edit distances with manageable computational overhead and without reliance on any public reference. Dynamic programming (DP) solves complex problems by breaking them down into smaller subproblems. For edit distance, each sub-problem involves computing the edit distance between increasingly larger subsequences of the original inputs. The Wagner-Fischer algorithm fills in a DP table D with each cell relying on the values of neighboring cells to determine the minimum edit cost for the transformation at that step.

An example is provided in the following image for sequences a = ATCGA and b = TCGTC. The DP table is structured as a 6 by 6 grid, progressing from the top-left to the bottom-right corner. In this table, each cell D[i, j] represents the edit distance between the subsequences ![]() and

and ![]() . The final entry, D[5, 5] = 3 (highlighted with a yellow background) indicates that the edit distance between the original inputs a and b is 3. Additionally, the yellow-highlighted path captures the minimum steps required for this transformation. The Wagner-Fischer algorithm efficiently computes edit distance, but genomic data’s sensitive nature poses significant ethical and legal challenges as traditional dynamic programming methods do not protect the privacy of the input sequences.

. The final entry, D[5, 5] = 3 (highlighted with a yellow background) indicates that the edit distance between the original inputs a and b is 3. Additionally, the yellow-highlighted path captures the minimum steps required for this transformation. The Wagner-Fischer algorithm efficiently computes edit distance, but genomic data’s sensitive nature poses significant ethical and legal challenges as traditional dynamic programming methods do not protect the privacy of the input sequences.

Secure multi-party computation (MPC) enables multiple parties to collaboratively perform a computation over their private inputs without revealing any information beyond the result. Unfortunately, the performance of generic MPC methods is closely tied to the efficiency of the underlying algorithm in the clear. In the case of edit distance, computing the minimum value of adjacent cells in the dynamic programming table is expensive under MPC (as it requires many comparisons), and careful consideration is needed to convert the cleartext algorithm to a privacy-preserving equivalent. Thus, we need to devise an optimized protocol for this use case. Another thing to keep in mind is that genome sequences possess distinct properties compared to sequences from a general alphabet, allowing for tailored optimizations when using MPC.

Exact vs Approximate Edit Distance Computation

The two main approaches in the field of secure edit distance computation either focus on exact ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , or on approximate computation.

, or on approximate computation. ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The latter approaches rely on the strong assumption of possessing a good public reference string for edit distance that enables parties to perform local computations (e.g., sequence alignment) to enhance performance. However, determining the reference string is not reliable in many cases – the performance of ED protocols highly depends on a reference string. Additionally, computing the exact edit distances is vital for healthcare applications that require precise results.

The latter approaches rely on the strong assumption of possessing a good public reference string for edit distance that enables parties to perform local computations (e.g., sequence alignment) to enhance performance. However, determining the reference string is not reliable in many cases – the performance of ED protocols highly depends on a reference string. Additionally, computing the exact edit distances is vital for healthcare applications that require precise results.

See our full paper for more details on exact and approximate edit distance-related works.

The SecurED framework for Secure Edit Distance Computation

In our work, we assume two parties, each holding a private DNA sequence, that want to compute the edit distance of their sequences without revealing any additional information. The possible edits include insertion, deletion, and substitution of a single character in the sequences. The edit distance between two sequences is defined as the minimum number of edits required to convert one string into the other (for example see the yellow path in the figure at the beginning of this blogpost). We’ve also already discussed the Wagner-Fischer algorithm for computing the edit distance in the clear. Although a straightforward privacy-preserving implementation would apply this algorithm in MPC, that would result in impractical performance due to the number of comparisons needed in each step.

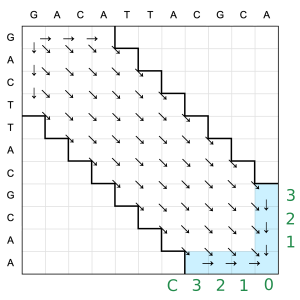

Ukkonen altered the WF algorithm and diminished time and space requirements, albeit with a minimal chance of inaccuracies in the edit distance result. ![]() In this approach, a threshold T is set, restricting computations to T diagonals extending in both directions from the main diagonal of the WF matrix. This can be visualized as:

In this approach, a threshold T is set, restricting computations to T diagonals extending in both directions from the main diagonal of the WF matrix. This can be visualized as:

where only 5 total diagonals are used (instead of 11 from before). The primary difference from the original WF algorithm is that updates are limited to the T leading diagonals. In this case, restricting calculations to T diagonals might miss parts of the optimal path, leading to an approximation. In practice, there is no good way to learn the upper bound of the edit distance for two arbitrary inputs. That is why a predefined parameter T leads to an approximation. Of course, a larger T gives a better approximation at the cost of more diagonals needing to be evaluated.

From Approximate to Exact: Achieving Precision in Edit Distance Computation

Genome sequences consisting of DNA nucleotides (A, G, T, C) exhibit properties that can be exploited when constructing an edit distance protocol:

- For arbitrary human genome sequences, it has been observed that over 99.5% of nucleotides are identical.

- When considering insertion, deletion, and substitution to transform one genome sequence into another, over 95% of edits are nonadjacent. Furthermore, within this nonadjacent edit set, approximately 80% to 90% of the edits are substitutions.

The first observation suggests that the edit distance is significantly smaller than the input size. The second observation implies that the path leading to the optimal output is likely to be near the leading diagonal. These characteristics make Ukkonen’s algorithm an excellent candidate for efficiently solving the edit distance problem over human genome sequences.

Our goal in SecurED is to compute the exact edit distance of two DNA sequences while maintaining the efficiency of approximate edit distance methods. Having the two aforementioned observations in mind:

- Our starting point is Ukkonen’s algorithm for approximate edit distance.

- Next, we introduce an efficient protocol for determining a precise edit distance upper bound.

This enables us to select an optimal threshold for Ukkonen’s algorithm, enhancing its performance while maintaining the accuracy of exact matching.

However, the Ukkonen algorithm with a threshold T may not yield an exact result. This is because, rather than computing all cells in the matrix, it only examines T diagonals adjacent to and including the leading diagonal. The immediate question that follows is: how can we efficiently determine such a threshold to enable exact edit distance computation from the Ukkonen algorithm? The main contribution of SecurED is to address the above question by proposing an efficient threshold determination algorithm. This approach transforms our main MPC-friendly construction into two phases. First, we determine a tight upper bound T′ based on a predefined loose upper bound T. Second, we utilize T′ as the threshold for the Ukkonen algorithm to compute the edit distance for genome sequences. Note that after being computed securely, the upper bound T′ can be seen as publicly disclosed information, as it can also be inferred from the final output. Selecting an excessively large upper bound can result in unnecessary computational costs for cases with small edit distances, while on the flip side, a smaller threshold increases the likelihood of approximation rather than exact computation for cases with larger edit distances.

We begin by solely focusing on paths that follow diagonals, accounting for only insertions (and deletions, as they are equivalent). Since we skip substitutions and comparisons, this pass is very efficient.

When we reach the end, we incorporate the additional cost to return to the leading (main) diagonal from each blue cell. This outcome is similar to determining the minimum edit distance involving substitutions only across T diagonals, incorporating insertions/deletions to both ends of the two sequences. Unfortunately, this approach over-approximates. For instance, consider the genomes ![]() = GACATTACGCA and

= GACATTACGCA and ![]() = GACTTACGCAA. The true edit distance between them would be 2, involving the insertion of A at the fourth position and the removal of A from the last position in

= GACTTACGCAA. The true edit distance between them would be 2, involving the insertion of A at the fourth position and the removal of A from the last position in ![]() . However, this approach results in 6, as shown below:

. However, this approach results in 6, as shown below:

To solve this problem, we break down our algorithm into segments and iteratively apply it in smaller partitions, rather than across the entire matrix. This allows us to periodically switch to the better diagonal and determine the minimum accumulation, as shown below:

In summary, our algorithm for determining the upper bound T′ takes a greedy approach. It breaks down large genomic sequences into smaller segments, computes the substitution distance for each segment, and, during checkpointing, adjusts it with the offset cost from the leading diagonal. Subsequently, for the following segments, the cost adjustment is made relative to the diagonal that had the minimum cost-adjusted distance. The loose upper bound T can be chosen to be a much higher value than what is feasible with the regular Ukkonen algorithm.

Now that we can find optimal thresholds, it’s just a matter of running the exact ED algorithm with the optimal threshold!

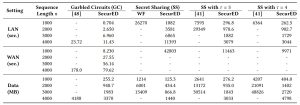

We instantiated SecurED with both garbled circuits and secret sharing and performed comparisons with related works. SecurED outperforms related works by a few orders of magnitude:

Check our paper for more experiments!

From Theory to Practice

SecurED brings secure edit distance computation from theory into real-world applications, allowing users to explore their DNA while ensuring privacy. As Monadic DNA puts it, “Privacy in genomics is no longer optional, it’s essential”. Monadic DNA enables individuals to encrypt their DNA data and leverage privacy-preserving genomic services, ensuring autonomy, security, and privacy. With SecurED and other privacy-enhancing technologies, Monadic DNA can offer end-to-end privacy for DNA sequencing, enable private family tree validation, and facilitate secure genomic matching for ancestry analysis, all powered by secure multiparty computation.

Check out the full podcast interview with Vishakh from Monadic DNA and Lukas and Juan from Nillion at https://x.com/nillionnetwork/status/1882050589317546210.

References

- Human Genome Project: https://doi.org/10.1038/35057062

- Personalized medicine references: Burke, W., & Psaty, B. (2007). Personalized Medicine in the Era of Genomics. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.14.1682

- Tsudik, G., et al. (2011). Countering GATTACA: efficient and secure testing of fully-sequenced human genomes. https://doi.org/10.1145/2046707.2046785

- Bruekers, F., et al. (2008). Privacy-Preserving Matching of DNA Profiles. https://eprint.iacr.org/2008/203

- Lindell, Y., & Rabin, T. (2018). Privacy-Preserving Search of Similar Patients in Genomic Data. https://doi.org/10.1515/popets-2018-0034

- Tran, B., et al. (2012). Cancer Genomics: Technology, Discovery, and Translation. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2316

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. (2001). Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. https://doi.org/10.1038/35057062

- Atallah, Mikhail J., and Jiangtao Li. “Secure outsourcing of sequence comparisons.” International Journal of Information Security 4 (2005): 277-287.

- Cheon, Jung Hee, Miran Kim, and Kristin Lauter. “Homomorphic computation of edit distance.” Financial Cryptography and Data Security: FC 2015 International Workshops, BITCOIN, WAHC, and Wearable, San Juan, Puerto Rico, January 30, 2015, Revised Selected Papers. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2015.

- Rane, Shantanu, and Wei Sun. “Privacy preserving string comparisons based on Levenshtein distance.” 2010 IEEE international workshop on information forensics and security. IEEE, 2010.

- Zhu, Ruiyu, and Yan Huang. “Efficient and precise secure generalized edit distance and beyond.” IEEE transactions on dependable and secure computing 19.1 (2020): 579-590.

- Asharov, Gilad, et al. “Privacy-preserving search of similar patients in genomic data.” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies (2018).

- Wang, Xiao Shaun, et al. “Efficient genome-wide, privacy-preserving similar patient query based on private edit distance.” Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 2015.

- Zheng, Yandong, et al. “Efficient and privacy-preserving edit distance query over encrypted genomic data.” 2019 11th International Conference on Wireless Communications and Signal Processing (WCSP). IEEE, 2019.

- Ukkonen, Esko. “Algorithms for approximate string matching.” Information and control 64.1-3 (1985): 100-118.

Follow @BuildOnNillion on X/Twitter for more updates like these